Are 2.35 films really more cinematic today? This is the question that I started to ask myself recently.

Are 2.35 films really more cinematic today? This is the question that I started to ask myself recently.

As I started to visit more of the theaters that are being built today, I started to notice something different. This is aside from my wife telling me that the screen uniformity was quite visible when we went to see Man of Steel when it premiered recently. The screen was closer to a 16:9 (1.78:1) aspect ratio than a 2.35:1 (21:9) aspect ratio. All the trailers before the actual film filled the screen and the commercials did as well. When the film actually started, black mattes dropped down from the ceiling and rose up from the stage floor to create the 2.35:1 aspect ratio for the Man of Steel film.

This gets me thinking about when the last time was that I actually saw a real 2.35:1 screen in a movie theater. And I can’t think of a single one in modern memory that used that type of screen in a native form. I recall growing up in the 70’s, 80’s and even the 90’s and visiting the theaters that just had the one marquee 2.35:1 screen. But when was the last time they actually built a theater with that type of screen in recent memory? The saying that “they don’t build them like they used to” would appear to be cruelly applicable to the state of theaters in the modern age. Is this a bad thing or a good thing? I’m indifferent here, but there are modern realities that we have to deal with.

Modern multiplexes don’t use 2.35:1 ratio screens anymore. They haven’t done so in years and years now. They are actually far closer to the TVs we have at home than the theaters of the old days. This is the norm now, not 2.35:1. I had a client recently who was in the theater management business as he worked with Cineplex/Odeon for the past 12 years. He oversaw the transition from film based projectors to the digital projectors that are in most modern theaters today. I asked him about 2.35 aspect ratio screens and if he recalled any theaters still using them. Answer. No. I commented to him that a lot of the screens looked suspiciously like 16:9 screens that most have at home now. He said that was right, but it wasn’t the only size that we would find in theaters. He said that the screens could often be all sorts of sizes even in one large multiplex facility. The screens only get sized out after they figure out the size of each theater so some may be even more squarish as a result; possibly closer to 1.33 screens. It’s whatever fits and some will have vertical mattes and others will be hard matted at the projector end.

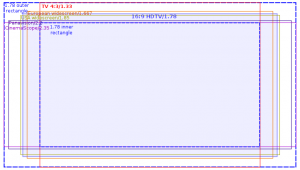

The graphic at the top of this article is a brief history of how the 16:9 aspect ratio actually came about in the first place. They took all the different aspect ratios that existed out there from the dawn of film and placed them all on top of each other, equalizing each rectangle for area. When that was done, a new rectangle was drawn along the outside edge of all these film aspect ratios and that was 1.78:1, well what do you know. 16:9 aspect ratio was the grand compromise for all films.

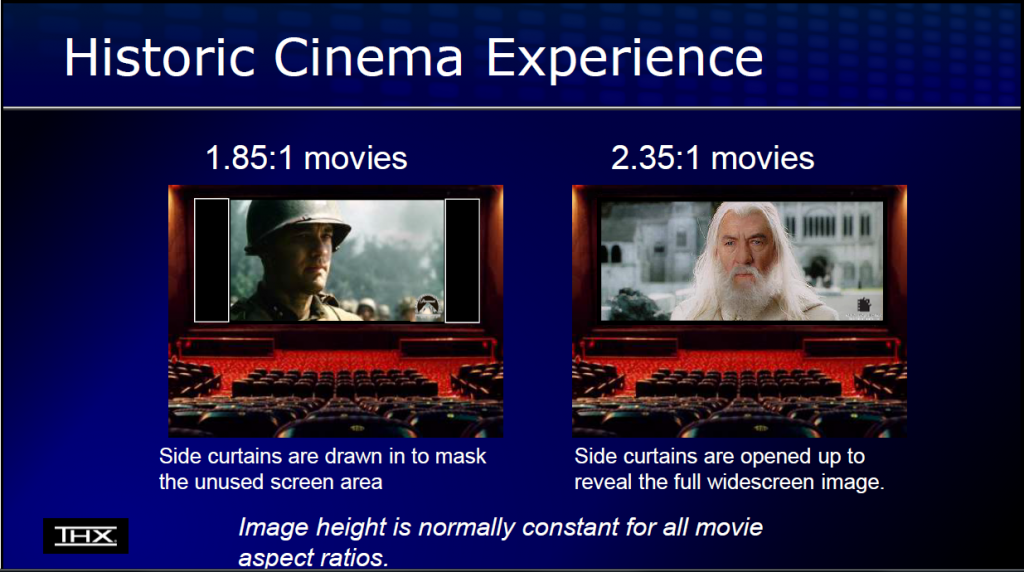

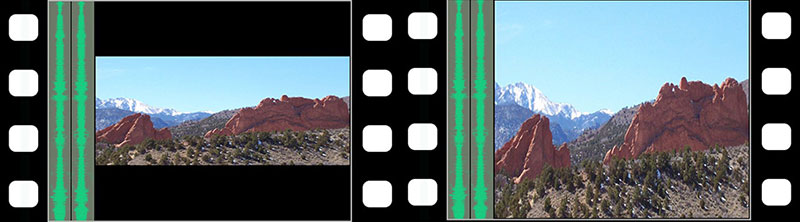

This gets us to the historic movie theaters that used 2.35 screens and are all but gone today. They looked like this. This slide comes with my thanks to Ken Bylsma at JVC.

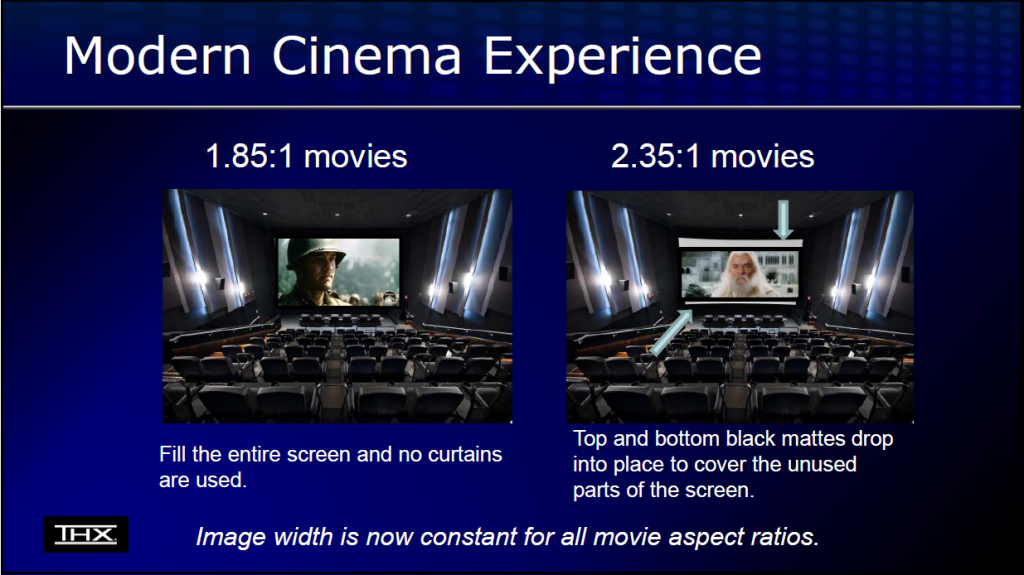

All the theaters built today do not really look like this anymore. In fact, they look more like the image below with the 16:9 screen. The scope films now are always smaller than the 1.85:1 films. It is no longer constant image height, but rather constant image width.

There are generations of kids growing up that only experience films through modern theaters and the 1.85:1 images are always bigger than the 2.35:1 films. Can we really definitively state that a 2.35:1 experience is superior to a 1.85:1 presentation? The 2.35:1 films are starting to emulate the home experience. They are now the films with the black bars on the top and bottom … seemingly wasting space. 🙂 Take the recent film “Pacific Rim” which was shot at 1.85:1 and really fits nicely on those 16:9 theatrical screens. It highlights the sheer immensity of the robots and the level of destruction caused by the sea creatures. Had such a film been presented at the 2.35:1 ratio, much of the impact would be lost.

The original scope films used the entire camera negative to reduce noise and grain and preserve detail. If you used less space on the 1.37:1 negative, then you wasted detail.

Film is an emulsion and has no pixel structure and has more resolution / detail than current digital projection. Film prints in most theaters are 3/4/5th generation prints. These are a copy of a copy of a copy. Real detail is lost with every copy you make so a typical 35 mm film frame that we watched in theaters had about an equivalent of 12 million pixels of detail. Of course only 1.5 million pixels ultimately gets to the screen due to projector shutters, lamp heat, screen perforation. (This article goes into more detail about resolution that we actually see in the theaters.) This is one of the advantages that modern digital projection has over film projectors.

Modern film production with digital cameras like the RED Cameras can just matte out the 2.35:1 frame composition on the 16:9 monitors they use or they can employ a number of anamorphic lens options that can make the film use up most of the available pixels on the imaging sensor of the camera. So called Scope films can be captured “flat” or with the special lenses. If they are flat, then they end up wasting a lot of the available pixels on the sensor of the camera. In our HDTV world, the 2.35:1 films use up about 1920×810 pixels or about 1.6 million pixels.

So with the use of anamorphic lenses, the full resolution of the camera sensor can be compressed into the 2.35:1 aspect ratio on the screen. The screen in the theater is still about 16:9 though so curtains come down from the top and up from the bottom of the stage to mask the rest of the screen. This 2.35:1 image is now just as detailed as the 1.85:1 films, but with a higher dots per inch count. (Much of this assumes that the film makers made the attempt to maximize the use of available pixels on the camera sensors. Because if they did not, then the DPI count could be closer to the 1.85 films or even less.)

The worse case scenario for shooting the 2.35:1 theatrical presentation is what actually is translated to the home environment in the form of our Blu Rays and such. There are no real Blu Rays that have this anamorphic process applied to them like in the early days of DVD where the box proudly proclaims that the film is “formatted for 16:9 displays.” If 2.35 films were actually formatted like this, then there would be a nice advantage to the people using the 2.35:1 screens since they would really be getting a more detailed image, not just a bigger one. (Projecting VHS tapes at HD resolutions like 1920 x 1080 does not result in HD detail. Well, Duh!) It would be an anamorphic lens only system though and zoom memory projectors could not take advantage of this. Only then we would have the true comparison of enhanced 2.35 films delivering two million pixels of real detail compared to the 1.6 million that a zoom memory system could deliver. More on the home side of 2.35 in this article.

But with movie theaters the way they are now in the digital age, the choice of shooting a film in 2.35 or 1.85 is purely an aesthetic choice rather than one form being inherently crisper or more detailed compared to the other. Want a movie that highlights how big things are … then 1.85 is the way to go … want one that highlights scenery and sweeping scope … then 2.35 is the best choice. The 2.35 choice will look almost exactly like the home experience where there are black bars and the film just does not fill the entire screen real estate.

The mixed IMAX type presentations where the film constantly switches from 1.85 to 2.35 are a perfect fit for these modern screens. (Dark Knight, Dark Knight Rises, Tron Legacy, Transformers 3, Mission Impossible 4) These types of presentations do not translate well at all in the home when people are using the 2.35 or 2.39 screens. So much for trying to emulate the theatrical experience.

Funny how the tables have turned on what are more sweeping images in the theater now.

Addendum – Oct 2013

And now a counter point to this article. A very interesting look inside the film industry at how the film makers feel about where the theaters are going. A case of what they ideally want and what is actually happening.

This comes from

John Schuermann

JS MUSIC AND SOUND

Owner, Lead Composer / Sound Designer